The Great New Orleans Fire of December 08, 1794

On any French Quarter walking tour in New Orleans, you will hear the story of the Great Fire of 1788. But the “other fire” of 1794 gets little attention. In 1794, the city of New Orleans was struck with a devastating fire as it was rebuilding from the first fire.

December 08, 1794 was the Feast of the Immaculate Conception, a holy day of obligation in the Catholic city. It is also traditionally a day when families gather and eat together, when workers have a day off, a sort of unofficial kick-off of the Christmas season. Probably told to get out from underfoot as their families prepared for a feast, some boys playing with flint and tinder started a fire, which soon ignited some hay in a stable. The blaze quickly spread, and in a few hours 212 structures in the city were in ruins.

New Orleans was at that time a city of about 6,000 to 7,000 people, including many recent arrivals from Haiti. The people of Spanish New Orleans were probably looking forward to the end of a pretty bad year. A malaria epidemic earlier that year had taken the lives of several citizens, and two hurricanes in August had caused fissures in the levees that separated the river from the town. Revolution raged in France and the future of the Spanish colony was uncertain. The streets of the city were choked with garbage and raw sewerage. The inventions that would change the economic climate of the city – the cotton gin, granulation of sugar, and the steamboat – had not yet been introduced.

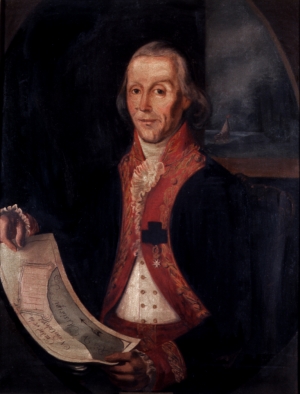

On the other hand, the energetic and organized Governor Carondelet was ending his third year in his position.  He had brought the first newspaper and the first theatre to New Orleans, work had begun on the canal that would make it easier to bring goods into the city, and, after more than six years of worshiping at a temporary church, locals were looking forward to the dedication of the impressive new St. Louis Church on the town square. The governor had also required a well dug on each city lot for pumps in case of fire, and little “bridges” of wood built over the ditches between the streets and the sidewalks (banquettes). New pumps, shipped from Philadelphia, would be utilized on the day of the 1794 fire, probably resulting in less damage that there would have been without them.

He had brought the first newspaper and the first theatre to New Orleans, work had begun on the canal that would make it easier to bring goods into the city, and, after more than six years of worshiping at a temporary church, locals were looking forward to the dedication of the impressive new St. Louis Church on the town square. The governor had also required a well dug on each city lot for pumps in case of fire, and little “bridges” of wood built over the ditches between the streets and the sidewalks (banquettes). New pumps, shipped from Philadelphia, would be utilized on the day of the 1794 fire, probably resulting in less damage that there would have been without them.

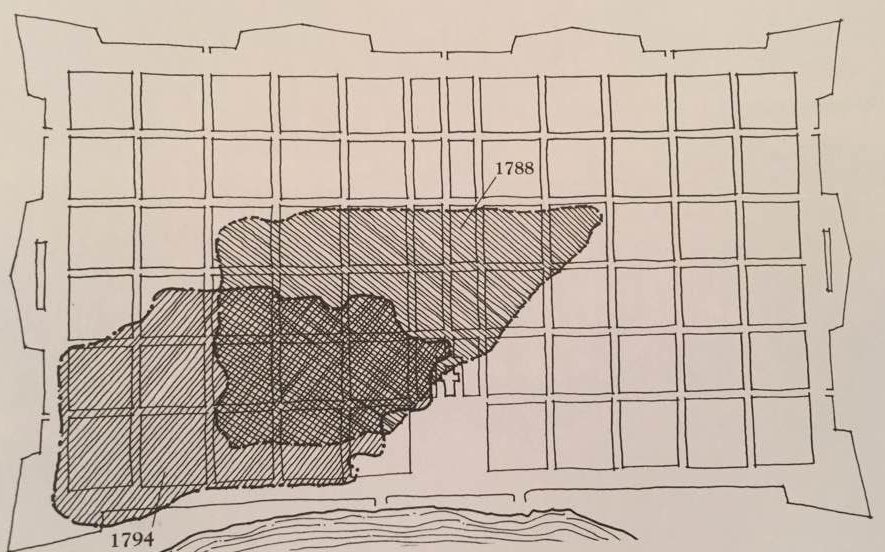

areas of 1788 and 1794 fires

Then, the fire. The blaze began in the same block that the 1788 fire had begun, so most of the structures destroyed were “the newest, most improved, and opulent,” according to reports of the time. The city jail was ruined. The warehouse containing the city’s entire store of wheat flour was destroyed, prompting us to go, for a moment, gluten-free. Looting began almost immediately after the chaos. Once tallied, the damage came to about 2.5 million dollars.

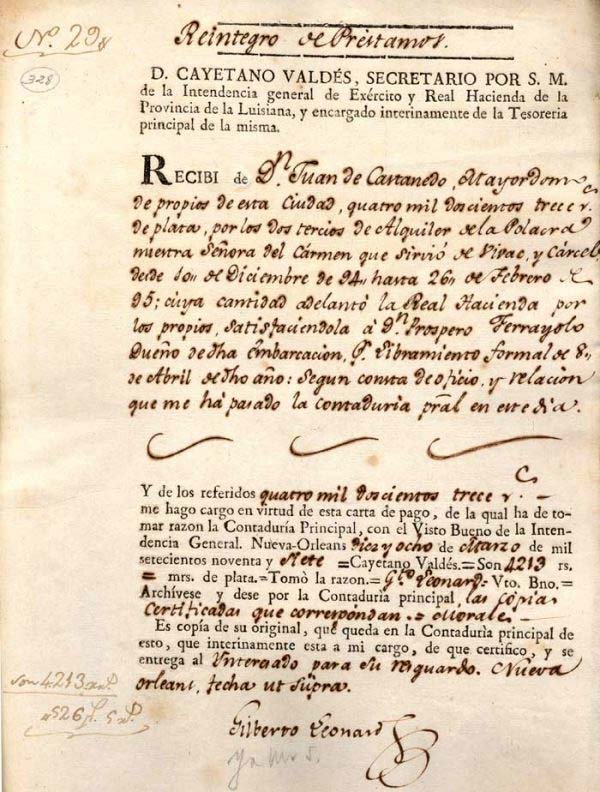

Receipt for the use of a schooner as the temporary city jail

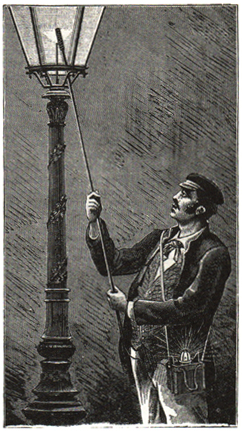

And, as New Orleans had done so many times before and would continue to do in the years to come, we rallied. On December 10, the city arranged with a local man to use his schooner, Nuestra Señora del Cármen, as a temporary jail. Cooks began to make calas instead of beignets. The new church was dedicated on December 23 and nearly everyone turned out for Midnight Mass on Christmas Eve. Governor Carondelet decided that New Orleans not only needed to be able to fight fires (and crime), but had to prevent them. He ordered 80 lamps from Philadelphia to light the town and had reflectors installed on buildings to increase the illumination. He hired night watchmen (or serenos) to tend to the lamps and be on the lookout for fires. The sereno s would be rewarded with a bonus for putting out a fire, and they also became the first police force of New Orleans. Soon, New Orleans began making its own lamps, which were fueled by fish oil, bear fat, and pelican grease. In order to cover the cost for this new fire-and crime-fighting force, Carondelet enacted a “chimney tax” on property owners. Much contested, this tax charged people for the number of chimneys on their property. Carondelet’s reasoning was that the wealthy would have bigger homes and more chimneys, therefore pay more tax, but, because so much new building was going to happen in the next few years, people found ways of getting two or sometimes three fireplaces from one chimney per story, therefore paying less tax. The fact that the chimneys in New Orleans are on the insides of buildings and not on the side has its root in Carondelet’s tax to pay for police and fire protection.

s would be rewarded with a bonus for putting out a fire, and they also became the first police force of New Orleans. Soon, New Orleans began making its own lamps, which were fueled by fish oil, bear fat, and pelican grease. In order to cover the cost for this new fire-and crime-fighting force, Carondelet enacted a “chimney tax” on property owners. Much contested, this tax charged people for the number of chimneys on their property. Carondelet’s reasoning was that the wealthy would have bigger homes and more chimneys, therefore pay more tax, but, because so much new building was going to happen in the next few years, people found ways of getting two or sometimes three fireplaces from one chimney per story, therefore paying less tax. The fact that the chimneys in New Orleans are on the insides of buildings and not on the side has its root in Carondelet’s tax to pay for police and fire protection.

The fire-waiting-to-happen straw huts that had been constructed after the 1788 fire for temporary housing and were now being used as low-income rental property were demolished.

The most lasting effect from the Great New Orleans Fire of 1794, in fact, is in the architecture of the French Quarter. The Spanish Crown bristled at having to pay to twice rebuild a city that had never produced any income for Spain. This time, strict building codes meant to prevent and retard fire were put in place. A new home could no longer have wood as its primary building material. The French had built the village mainly out of old-growth cypress, which was abundant in the swamps that surrounded the city. Cypress, impenetrable to water and excellent for dugout canoes and vats for shipping  liquids, has a high resin content and is therefore very flammable. Now all the buildings were to be of brick with a flat or tile roof. Houses were no longer set back from the street, out of reach of the portable water pumps. Carriageways and alleyways provided emergency access to the wells and cisterns in the courtyards of the new houses.

liquids, has a high resin content and is therefore very flammable. Now all the buildings were to be of brick with a flat or tile roof. Houses were no longer set back from the street, out of reach of the portable water pumps. Carriageways and alleyways provided emergency access to the wells and cisterns in the courtyards of the new houses.

The Spanish were only to be in possession of New Orleans for another nine years, but by the time of the Louisiana Purchase, the city was in the early stages of an explosion of economic, population, and cultural growth, and had come to identify the Spanish Colonial building styles with its Creole identity. So even after the Spanish building codes were no longer law, the style of building in the oldest part of the city continued.

There were some changes and some ways the locals made it their own: namely, in the look of the roofs and the balconies. The flat roof was impractical in a region which gets an average of 60 inches of rain per year, so it was soon replaced with pitched roofs. People no longer had front yards, so  they began to build balconies and galleries on their urban buildings to have some outdoor space, a place to catch a river breeze, talk to your neighbor, let a basket down to buy something from a street vendor, or, in the hottest months, drag a mattress out and sleep at night.

they began to build balconies and galleries on their urban buildings to have some outdoor space, a place to catch a river breeze, talk to your neighbor, let a basket down to buy something from a street vendor, or, in the hottest months, drag a mattress out and sleep at night.

To learn more about the history, culture, and architecture of this great neighborhood, sign up for one of our great New Orleans walking tours. We would be delighted to show you around!

Libby Bollino

Lucky Bean Tours

New Orleans